Two poems out at The /tƐmz/ Review

The /tƐmz/ Review has kindly published two “minimalist” poems from my manuscript-in-circulation Blank Song, “Epitaph” and “Ars Poetica: the eloquence of the vulgar tongue: ‘The top global stories that matter’.”

You can read them, and many other poems and stories, here.

Poetry Month—2025

April is National Poetry Month, and it will (“cruelly”) be observed in an overwhelming number of ways. These observations will invariably (and for obvious reasons) take poetry as an art form and in terms of its place in the world as a given, unproblematic. But is the matter really so simple?

In the lecture “What Are Poets For?” (first delivered in 1946, later revised, collected, and published in Holzwege in 1950), Martin Heidegger says of those poets in dürftiger Zeit (literally, “a desperately impoverished time”) that “It is a necessary part of the poet’s nature that, before they can be truly a poet in such an age, the time’s destitution must have made the whole being and vocation of the poet a poetic question…” Heidegger’s compatriot, Theodor Adorno (for all their differences), expresses a similar thought in his unfinished Aesthetic Theory (1970): “It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident anymore, not its inner life, not its relation to the world, not even its right to exist.” Have matters changed so much since? Is poetry—as an art, in the vocation of the poet—today now so self-evident in its “inner life,” its “relation to the world,” its “right to exist”?

One might be forgiven, of course, for suspecting these philosophers of not taking poetry or Dichtung (roughly, literature) seriously, dismissing it, as have many philosophers since Plato, who accused poets of being liars. Of course, in the case of Heidegger and Adorno, such suspicions would be unfounded. During the Second War, Heidegger famously turned to Hölderlin as a primary source of his thinking, and Adorno, throughout his career, wrote not only (and at length) on music, but on literature, as well, as the volumes of his Notes on Literature attest. One might even venture that Adorno pointed to Samuel Beckett (especially his novel The Unnameable) as a poet (Dichter) for our dürftiger Zeit.

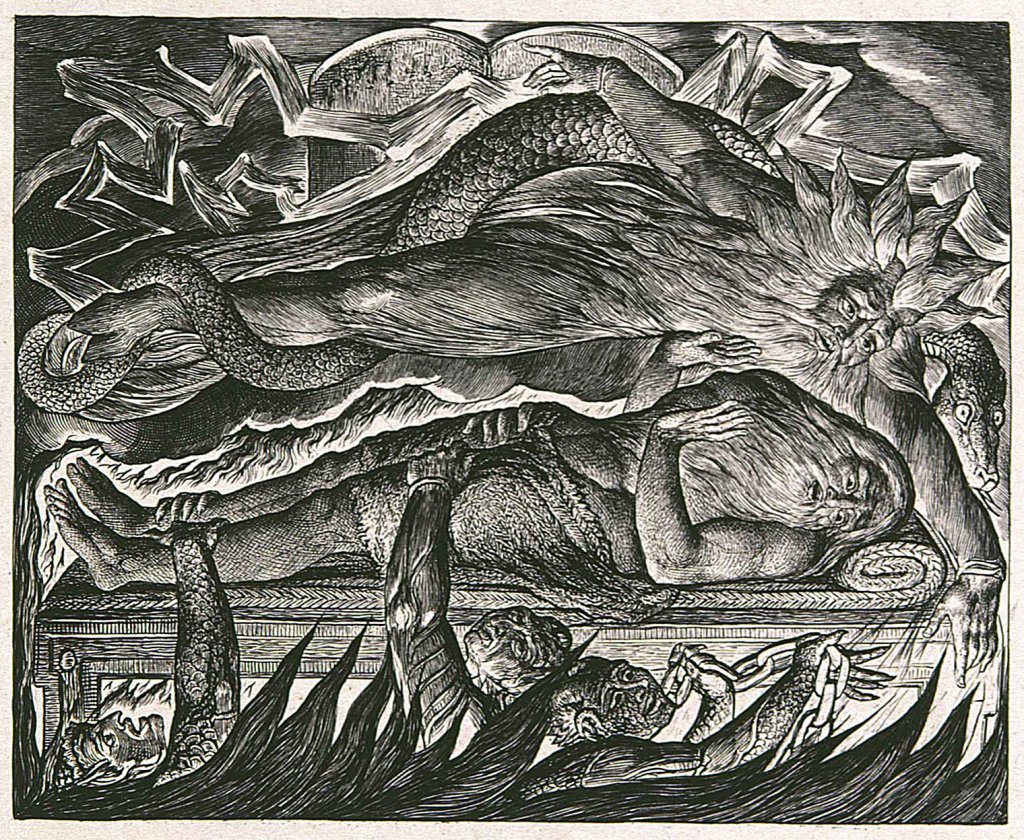

What makes the time, at least of the two philosophers here, so “destitute”? What has pulled the rug from under, if not removed the very ground beneath, the “self-evidence” of art? Heidegger delivered the first version of “What Are Poets For?” at the end of 1946. Germany and much of Europe lay in ruins, Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been reduced to radioactive ash, and the horrors of the Holocaust were coming to international light. In March of the same year, Winston Churchill had already spoken of “the Iron Curtain.” By the time of Adorno’s death in August, 1969, matters had arguably worsened. Not only had the Cold War intensified, raising the risk of Mutually Assured Destruction, but the ecological crisis was becoming a cause for concern, all aggravated by the developed world’s being increasingly, suffocatingly administered under the rule of technocratic, instrumental reason. From the point of view of Geist (“spirit”), even before 1946, radio, recorded music, and cinema, indeed commercial media had begun to displace so-called “High Art,” a development impacting T. S. Eliot’s The Wasteland (1922) and bewailed at length and in detail by critic F. R. Leavis. By the time of Adorno’s death, television had been added to this mix, cultural production “proximally and for the most part” now determined by the “Culture Industry.” The grounds for Adorno’s declaration, above, are arguably more involved (such was the sophistication of his thinking), but the desperation of their time, the beginning of our own present, desperate time, is not difficult to discern.

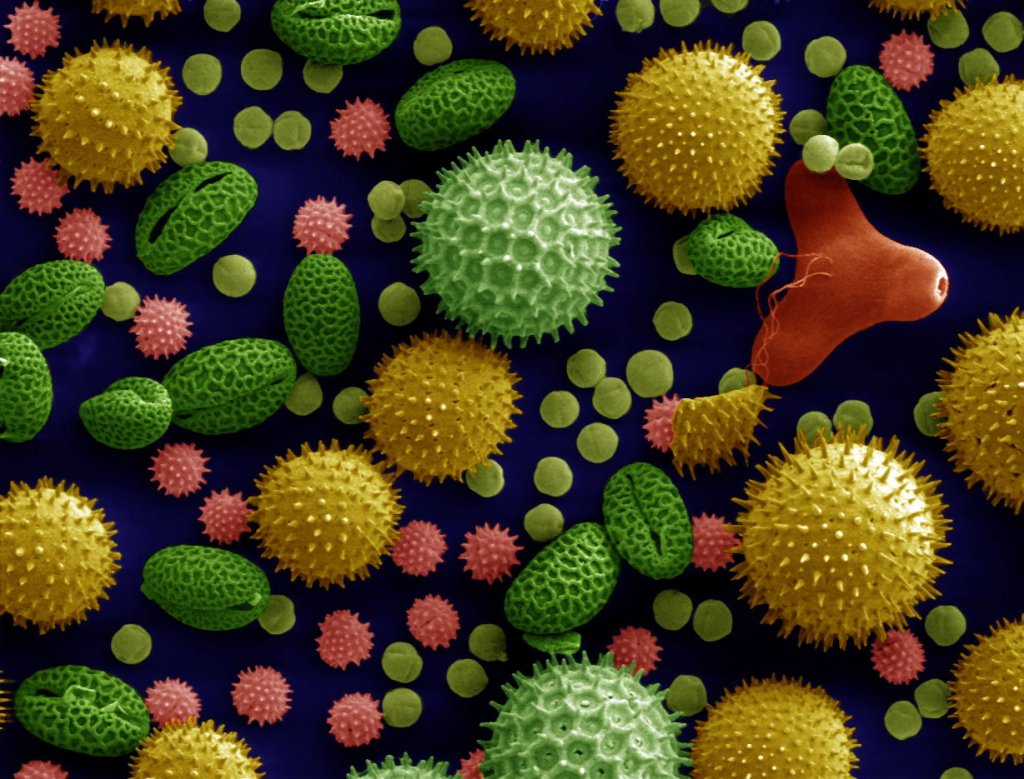

And today? The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is at its highest point in 800,000 years, pushing the climate out of the temperate, post-Ice Age Holocene, the matrix for human civilization as we’ve known it, into one Homo Sapiens have never inhabited. Micro- and nanoplastics contaminate every cubic centimeter of soil on earth and every tissue in the human body, including the brain. That brain’s capacity for attention and focus has been disrupted by digital media, which has whipped the public sphere to a froth. Just before the Second War, Yeats famously wrote that “the centre does not hold.” Not long before, the human capacity to know nature arguably hit a limit in the paradoxes of the quantum realm, and human reason, at least in its logical aspect, foundered at its limit, drawn by Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem. Ironically, what could be known of, or at least drawn from, that same quantum realm, enabled the detonation of the A-bomb, simultaneously enabling humankind to destroy itself and creating a never-before-seen mineral, Trinitite. Not only has the ground fallen from beneath us (in the limits discovered to physics and logic), but the future is at best unknown and at worst foreclosed. For all its often plodding portentiousness, Heidegger’s essay understands the dürftiger Zeit in Hölderlin’s “Bread and Wine” as a night nearing midnight, a reaching into the abyss; from this present moment, a prophetic insight. What in this now is self-evident in its “inner life,” “its relation to the world,” its “right to exist”?

Another poet, Rimbaud, writes that “we must be absolutely modern,” a statement as descriptive as prescriptive. On the one hand, we can’t help but be “absolutely modern,” of our time, a moment so intimate knowledge of it eludes us, that which is closest being farthest away, as Charles Olson paraphrases Heraclitus. Despite our inescapably absolute modernity, we are always too late, especially in our hypermediated present, when everything happens too quickly (culturing that modern malady of the Fear-of-Missing-Out). That “we must be absolutely modern,” then, becomes a condition for our meeting, living up to (if not through) our present, desperate predicament. In absolutely modern terms, Hölderlin’s question, Wo zu Dichter in dürftiger Zeit? (“What are poets for in a destitute time?” in one translation), becomes, in part, What are poets, what is poetry, for on a planet humankind has never inhabited (and may not inhabit for long)?

If we are to observe (as we have a little here), let alone celebrate, National Poetry Month, we might do so a little more “cruelly,” facing, squarely and clear-eyed as possible, the predicament of the moment and its consequences for the art of poetry and its place in it. Surely, however, such a challenge doesn’t call for (critical, let alone “philosophical”) reflection alone: responding to the desperation of a time that calls everything—and poetry with it—into question might equally call forth poetry itself, just no longer a poetry harmonious and fit with an era irretrievably fallen into the abyss of the past, but one aspiring to be equal to—as new, as modern—as our unprecedented moment and, hopefully, future. Only a poetry that surrenders its complacent self-understanding and confidence in its place in the world—a world long gone—can begin to remake itself as poetry—poiesis, making—uncanny (unheimlich, no longer at home), unrecognizable—yet, thereby, something recognizably made new—alive to a moment that might be imagined to need it most.

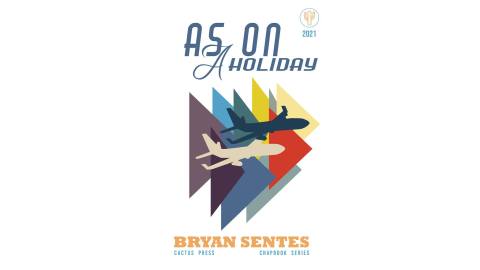

Hell’s Printing House: As on a Holiday (2021)

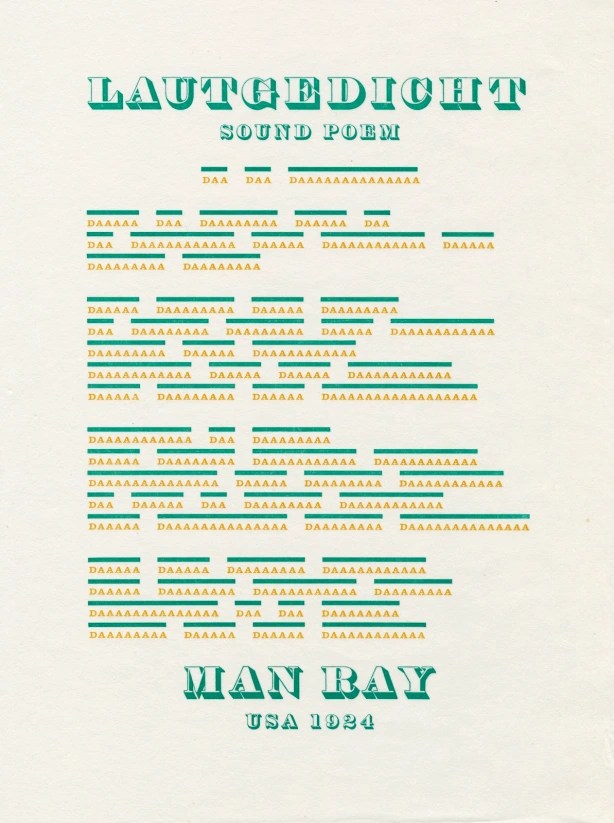

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

It’s appropriate that this final (for the time being) installment of Hell’s Printing House, like the first, should be of a book published not by myself.

I’m uncertain, now, if the editors at Cactus Press solicited a chapbook or merely opened the door to my submitting. At any rate, I found myself sorting through that big pile of unpublished poems for a selection that might, in some manner, cohere. As I’ve been fortunate enough to be both gainfully employed and to be married to a woman born in Germany, I’ve often found myself visiting various locales in North America and Europe, so collating the poems and sequences often written on these jaunts proposed itself.

The chapbook’s title alludes to a poem of Hölderlin’s “Wie wenn am Feiertage…” The book opens with an epigraph from the the Old English Widsith or Traveller’s Song: “Swa scriþende : gesceapum hweorfað / gleomen gumena : geond grunda fela” (Wandering like this, driven by chance, / minstrels travel through many lands). The book’s contents are:

- “SONOT: Lakeside Estate”

- “Made in Germany” un carnet de voyage

- Farnad Songbook

- Toronto Suite

- Qu’Appelle Valley Elegies

Though not even two-dozen pages of very short poems, those poems are often dense with reference and allusion (as if the title and epigraph didn’t already make that clear…). Readers of a certain education or reading, in the opening cantos of Qu’Appelle Valley Elegies might detect nods to Rilke (as remarked, below), Petrarch, Eliot, and Yeats, whose “Wild Swans at Coole” is echoed in the sequence’s second canto, “White Pelicans on Pasqua.” The chapbook poems’ brevity is quite intentionally balanced at times by just such a depth of what all-too-often is clumsily termed “intertextuality.” Nevertheless, more generally, the truncated expression is governed by a strict, metonymic economy.

The collection is book-ended by poems inspired by stays at my best friend’s home on the shores of Pasqua Lake, Saskatchewan. My times there have been so herrlich, that I’ve felt at times like Rilke staying in Duino Castle, hence the title of the book’s closing sequence. The second sequence recounts a trip overseas made in 2012, the year student demonstrations—the Maple Spring—filled Quebec streets. Farnad Songbook is a sequence composed during a summer stay at another friend’s European digs. And Toronto Suite was likewise composed during a long weekend getaway to the cultural capital of Canada (or, at least, its centre of power…).

Many excerpts from As on a Holiday can be read and heard on Poeta Doctus: from “Made in Germany,” “Waiting on a train…” and “http:// arctic-news.blogspot.de…” (both of which you can hear, here), and “London intermezzo;” the opening poem from Farnad Songbook (recorded, here); from Toronto Suite, “In the Royal York’s Library Bar…,” “Toronto Spring 2018 Getaway Takeaways,” and “Literary Life in the Capital” (recorded, here).

To mark the chapbook’s launch, I read its entirety, here.

Hell’s Printing House: Blank Song & other poems (2017)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

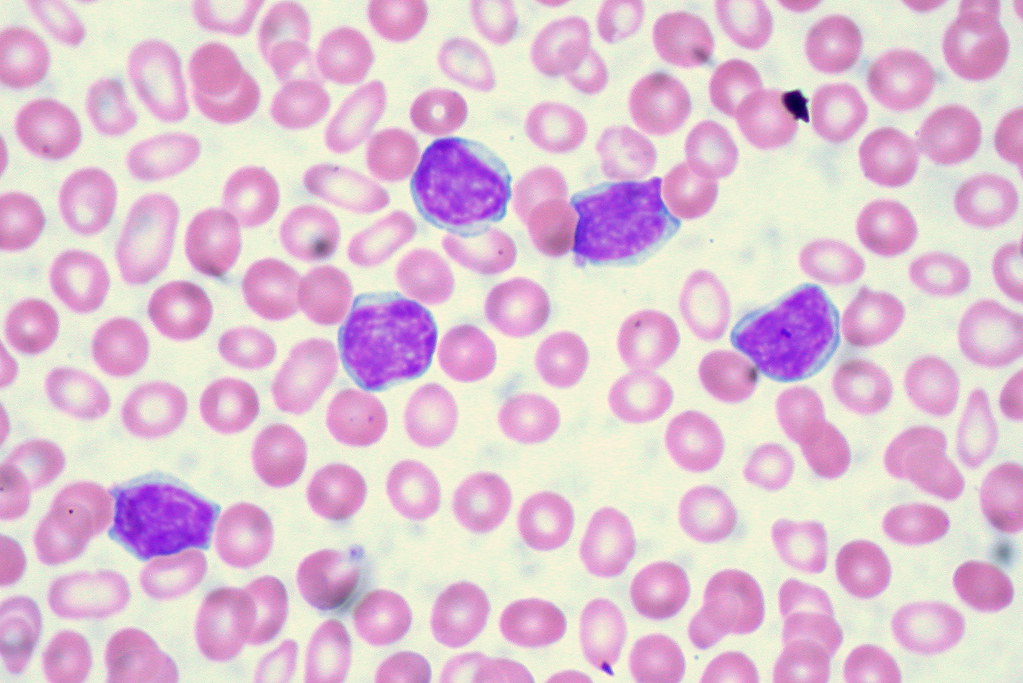

June 13, 2013 I was diagnosed with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and in May, 2016 started a six month chemotherapy regimen. Some (very few) poems resulted. The late, great Ian Ferrier, a Montreal-based poet and impresario, kindly invited me to read at his Words and Voices series in November, 2017 and, for the occasion, I collated a sequence about my cancer experience to that point, Blank Song, along with five other poems. In February, 2023, The Typescript published three poems from that sequence.

The title puns on the French sang blanc, “white blood,” a reference to ‘leukemia’, the name given my blood malady (from Greek leukos “clear, white” and haima “blood”). (A native French speaker tells me the French puns, further, on ‘semblant‘). But “blank song” also nods to a stylistic development, a tendency (apparently) to the plain spoken; understated, litotic or laconic; metonymic rather than metaphoric. Despite this eschewal of present-day, poetic fashion with its tendency to certain manners of surface complexity, there remains an undercurrent of allusion and other manners of linguistic and rhetorical complexity.

The (very short) sequence “Blank Song / sang blanc” spans an initial reflection on my predicament on American Independence Day, 2013 through my undergoing chemotherapy three years later, six poems in all: “Day after I’m told,” “I’m fifty-two…,” “Instead of saying…,” “No point…,” “The Chemical Brothers,” and “Independence Day 2013.” The other, miscellaneous poems are

- “What does it mean…”

- “She admits she has no sense of humour…”

- “Chez La Chronique“

- “My Brother the Doctor Visits After Too Long,” and

- “Life can change so quickly”

I post the the sequence Blank Song / sang blanc, followed by a reading.

Next month: As on a Holiday (2021).

Hell’s Printing House: In Canus Major (2009)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

As usual, the two short poems and two sequences this chapbook collects were collated for a poetry reading the summer of the year in the subtitle.

They were collated according to their shared influence, under the sign of the Dog, which is acknowledged in the title’s resonances. One the one hand (paw?), the title refers to the constellation; on another, it suggests that the poems are composed in the key of the Dog. As well, the “title track” is titled “Dog Days.” The “dog” here is Diogenes the Cynic (pictured on the cover), whose given name rimes with ‘dog’ (“dog-genes”) and whose title is derived from the Greek kynikos, literally “dog-like,” from kyōn (genitive kynos), ‘dog’. The original Cynics were termed so because of their shameless behaviour, including urinating, defecating, masturbating, and copulating in public. (Interested parties are urged to consult The Cynics: The Cynic Movement in Antiquity and Its Legacy, eds. Branham and Goulet-Cazé, the volume which informs the take on Cynicism at work, here).

The poems/sequences collected are

- “Welcome Home”

- “Intimations of Mortality”

- “Moundt Royall one circuit”

- “It’s not that you’re young and pretty…”

- “I want to know…”

- “Re: De Rerum Natura IV: 1052-1287”

These last three poems are the sequence remarked above, “Dog Days,” now subtitled “after Corvus Sanctus the Cynic (fl. 64 BCE),” a subtitle intended to underline the poems’ stemming from the traditions of both Cynicism and classical Latin poetry, especially that of Catullus and Juvenal, both known for their forthright, unapologetic bawdiness.

I read this sequence, here.

Next month: Blank Song and other poems (2017?):

The Serpent and the Fire and Louis Riel

This month marks the publication of the final assemblage of Jerome Rothenberg (with co-editor Javier Taboada), The Fire and the Serpent.

As the publisher’s website tells us:

Jerome Rothenberg’s final anthology—an experiment in omnipoetics with Javier Taboada—reaches into the deepest origins of the Americas, north and south, to redefine America and its poetries.

The Serpent and the Fire breaks out of deeply entrenched models that limit “American” literature to work written in English within the present boundaries of the United States. Editors Jerome Rothenberg and Javier Taboada gather vital pieces from all parts of the Western Hemisphere and the breadth of European and Indigenous languages within: a unique range of cultures and languages going back several millennia, an experiment in what the editors call an American “omnipoetics.”

The Serpent and the Fire is divided into four chronological sections—from early pre-Columbian times to the immediately contemporary—and five thematic sections that move freely across languages and shifting geographical boundaries to underscore the complexities, conflicts, contradictions, and continuities of the poetry of the Americas. The book also boasts contextualizing commentaries to connect the poets and poems in dialogue across time and space.

Included in the volume’s vast spatiotemporal range are poems by bp Nichol and Nicole Brossard, along with a contribution by myself and Antoine Malette, translations of some sections of Louis Riel’s Massinahican. To whet your appetite, I invite you to sample that translation and some remarks about it, here.

And, as an added bonus, I invite you to save 30% when you purchase a copy of this book from the University of California Press website: just enter code EMAIL30 at check out. (Hopefully the cost of shipping and handling won’t negate the savings…).

Hell’s Printing House: Melathalassemia: Tristia from March End Prill (2009)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Melathalassemia is another of those chapbooks binding poems for a performance. I forget now who kindly invited me to read, though I do seem to recall it was winter. Perhaps the season prompted my collecting the sections from March End Prill that concerned melancholy (supplemented by two miscellaneous poems on the same theme, “Corpomancy” and “Hymn”).

The title is a coinage, intending to signify, roughly, “Black Sea meanings,” invoking the “black blood” of melancholia and Ovid’s exile in Tomi, underlined by the subtitle’s naming these poems “tristia.” I was especially fortunate to have this chapbook designed my Maurice Roy.

None of these poems have been shared here at Poeta Doctus. Melathalassemia gathers nine poems from March End Prill along with the two mentioned above. The poems from March End Prill are

- “A Cut to Bear Night Thought”

- “Black milk…”

- “Born…”

- “Soul inanimate…”

- “Black blood…”

- “Anatomize…”

- “Aren’t there any cookies…”

- “dustmice taken…”

- “imagine snorkeling…”

“Hymn” (one of the two poems not from March End Prill) is taken from a text composed daily over one lunar cycle sometime before 1999. When I shared it with some members of the Hungarian-language Arkánum group, one remarked of this particular text, “That could be a hymn!” hence the title. His recognition of the text’s being at all poetic I take as sufficient blessing to share, here. I read this poem (presently filed away in a folder titled “Carmina Nongrata” on my computer), below.

Next month: In Canis Major (Summer 2009).

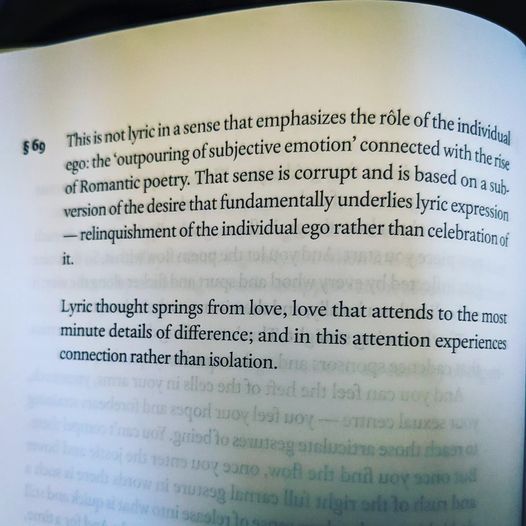

A Metonymic Ideogram Concerning Poetic Attention

I’ve resisted writing the following, but a small flurry of persistent synchronicities insists otherwise.

It began with a Facebook discussion thread, prompted by a Canadian anglophone poet of my acquaintance. “Saw the list of this year’s Griffin judges. If we have a Canadian nominee other than Michael Ondaatje’s poetry collection A Year of Last Things I will be surprised.”

Around the same time, I happened on a remaindered copy of Hans Blumenbergs’s Work on Myth, and two poetry collections by Daniel Borzutzky (The Ecstasy of Capitulation and The Performance of Becoming Human) arrived, along with Jerome McGann’s The Point Is to Change It: Poetry and Criticism in the Continuing Present.

In the opening pages of McGann’s book “The Argument,” McGann observes “[Walter Benjamin and Gertrude Stein] both approach the history of poetry as an emergency of the present rather than as a legacy of past. The emergency appears as a poetic deficit in contemporary culture, where values of politics and morality are judged prima facie more important than aesthetic values.” Regardless of one’s knowledge or opinion of Benjamin or Stein, McGann’s invocation of “emergency” is provocative, to thought and otherwise.

Then, today, Norman Finkelstein’s Restless Messengers posted a three-part piece on Michael Boughn, a brief introduction by Miriam Nichols along with a review of his latest poetry book and a book of essays (by Finkelstein, required reading). Reviewing that poetry collection, The Book of Uncertain A Hyperbiographical User’s Manual (Book One), the reviewer, John Tritica, remarks “Michael Boughn does not write what Jack Spicer called one night stand poems, those shiny, reader-friendly, award-winning, readily consumable poems so prized by mainstream anthologies and awards institutions.”

Readers with an ideogrammic/metonymic sense will surmise what I’m on about here. I’ll let this juxtaposition speak for itself…

Hell’s Printing House: Symposia Scholia (2006)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

It’s seemed to me for some time now that very little anglophone poetry surpasses the compositional innovation of The Wasteland. That is certainly true of much of my own poetry, which is often, thoughtlessly, pegged as “experimental.” Being a reader of Ezra Pound as long as I’ve been a poet, little surprise, then, that I might mine the ideogrammic vein Pound first prospected, writing poems that are fragmented and polyphonic (in a manner, however much more minor, of The Wasteland). One inflection of this method appears in Ladonian Magnitudes, “Elenium.”

The parts of the poem collated as Symposia Scholia are composed in the same way, collaging striking scraps of conversation torn from good times spent with friends. The poem’s title invokes this inspiration, ‘symposia’ the plural of ‘symposium’, drinking party, and ‘scholia’ the equally antique Greek for “drinking song.” That the interlocutors were often learned is further implied by the modern connotation of ‘symposium’ and the rime of ‘scholia’ with ‘school’, ‘scholar’, and ‘scholarly’.

The poem bound in the chapbook has the following parts:

I. Madrigal

III. The third who talks beside us

IV. The Séance: a Rawdive Fugue

V. Rose Hill

That the poem appears, thus, incomplete is intentional (the same is true for the sequence Táncház), an incompleteness intended, in part, to mirror the reader’s own feeling of failing to get a firm interpretive grip on the poem’s parts, highlighting the way that any object, linguistic or otherwise, must finally elude a complete, final, “absolute” knowledge.

However much the poem fails to escape the gravity well of The Wasteland, I would point to even older influences. The form here rimes, in its own way, with the practice of the Jena Romantics in their collations of fragments published in The Athenaum. There, the collective effort wherein the individual contributors remained anonymous was intended to enact a symphilosophy. Nor should the theme of Plato’s dialogue The Symposium, eros, be thought irrelevant. And these rimes with symphilosophy and Platonic dialogue all fold into the contemporary concern with thinking-as-conversation so magisterially explored by the late Hans-Georg Gadamer (to whom a poem is dedicated in the latest poetry manuscript making-the-rounds…).

Symposia Scholia was short listed for the 2019 Gwendolyn MacEwan Poetry Prize.

Below, a version of the poem’s final section, “Rose Hill,” followed by a reading of it.

Next month: Melathalassemia: Tristia from March End Prill (2009).

Hell’s Printing House: Táncház: Hungarian Dance House Festivals V, VII, X, XI, XII (2005)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

I cannot recall now what prompted me to pick up Joseph M. Conte‘s Unending Design: The Forms of Postmodern Poetry (Cornell University Press, 1991) soon after it was published. The price pencilled in on my copy’s flyleaf indicates mine is a used copy. As I remember it, I was motivated by my having heard him deliver a lecture at Concordia University’s Liberal Arts College; however, he seems not to have spoken there until 1997. Nevertheless, perhaps it was the book’s Table of Contents (even more intriguing, today), with its attention to those poets I was interested in at the time, primarily Robert Duncan and John Cage. I can say with greater certainty that it was the book’s fifth chapter, which examined the use of a “generative device” in the work of William Bronk and John Cage, that motivated the composition (no later than March, 1992) of the poems collected here as Táncház.

After composing five “dance house festivals,” I wrote the following “note on composition”:

Starting in the 1980s a new generation of Hungarian folk musicians and dancers began to gather regularly at what came to be annual Dance House (Táncház) festivals. Song and dance titles recorded at some of these festivals are here the melodic lines to which the words in a sheaf of canonical Hungarian poems in translation sent me by a friend then living in Budapest are set. If “every language is a world” then the world in these festivals is one sung by the Hungarian poetic imagination to a tune and in a syntax both as foreign as non-Indo-European Hungarian traditional music and language are to the musics and languages of the rest of Europe.

That is, I formulated a rule whereby the song titles chose and arranged words from that song’s lyrics. That rule is, in part, present in the lines’ capital letters (which one early reader found “irritating”), intended to draw the reader’s attention, first, to the materiality of the language (already foregrounded by the poems’ non-normative syntax), then, to an awareness of a syntax or at least a syntactical rule at work governing what might otherwise (without sufficient effort) seem mere nonsense. Hungarian speakers might discern further resonances…

More, however, is at stake, as I went on to explain, in an appended collage of Ezra Pound, John Cage, the Jena Romantics, and others:

Most arts attain their effects by a fixed element and a variable: poetry is not prose because poetry is in some way formalized. Poetry is republican speech: a speech which is its own law and end unto itself, and in which all parts are free citizens with the right to vote: language speaks: Bacchus’ priest proclaims his feast, woe to infidels!

The words of that final sentence are my own, intended to underline the festive (anarchic) aspect of the language in these poems, what Novalis writing of language-as-such in his “Monologue” termed “närrische“, an adjective related to the noun Narr, referring to the “fool” of Karneval…

At the moment, I can’t remember, exactly, why I issued a chapbook of these poems. Since their composition, I’ve been able to find only one editor, Karl Jirgens, who appreciated them. “Táncház X” appeared in Rampike 17/2. The sequence of five is presently the final part of a manuscript-in-process, tentatively titled Fugue State, which includes a reworked version of X Ore Assays and Seventh Column.

Here, the first “Dance House Festival” composed, X, with an interpretive performance, following.

Next month: Symposia Scholia (2006).

New Poem up at Canadian Literature

Canadian Literature (#256) has very kindly published my poem “By Mullet River” (with commentary!) in its latest issue. You can read that poem, and all the other poems, reviews, and articles, here.

Hell’s Printing House: A Crow’n’ o’ Sough Noughts (2004)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

It was July 1991 I sat down one morning in a more relaxed compositional mood and wrote the following poem.

It was only after I had written these lines that I remarked there were fourteen. This unconscious compositional chance was fortuitious, for, as I’ve previously remarked, the sonnet sequence was all the rage in Canadian anglophone poetry circles at the time. Recently, I’d read, too, Charles Bernstein on Ted Berrigan’s sonnets along with the sonnets themselves, and I remembered having read much else about the history of the form, all of which was brought into focus by William Carlos Williams’: “all sonnets say the same thing.” What this vortex suggested to me was a nonintentional, chance-governed satirical practice: I wouldn’t set out to write “sonnets” or poems of fourteen lines (which many of the “sonnets” written at that time amounted to) but, rather, when I by chance wrote a poem of fourteen lines, I’d dub it a “sonot,” “soughknot,” or “soughnought” (‘sough’: the high or low long sound that something such as the wind or sea makes as it moves”)…

Over time, these sonots accrued. Some appear in the chapbooks to date, two are collected in Grand Gnostic Central (DC Books, 1998), and two dozen (as soughknots) in Ladonian Magnitudes (DC Books, 2006). I don’t know how many more I have written since. In the publishing lull following Ladonian Magnitudes, that fashion for sonnet sequences unabated, I was moved to gather twenty-five soughnoughts in a chapbook under the punny title A Crow’n’ o’ Sough Noughts. The collection is prefaced by a short epigraph: “A place to stand / A corner to loiter // To listen to the small / Sounds around.” Those not unacquainted with the etymologies of ‘sonnet’ will understand. On a visit to Ottawa at the time, I gifted a copy of the chapbook to one of Canada’s most prolific poet/reviewers, on whom, sadly, the joke—of both the epigraph and the collection as a whole—was lost, a too common reception…

Below, the table of contents. An asterisk marks those soughnoughts collected in Grand Gnostic Central, two, those in Ladonian Magnitudes. Those already shared here at Poeta Doctus are, of course, linked.

- “A piss…”**

- “Church bells ring loud…”**

- “Clear nights I look up…”**

- “Come out of the cave…”**

- “Comn home th’other afternoon…”**

- “As I delighted with the enjoyments of torment…”

- “Every afternoon I lie on the couch…”

- “Grave as Spring is green…”**

- “I HATE POETRY”**

- “I know the ‘aurora borealis’…”*

- “20:02 20.02.2002” (“Inside / dark out…’)**

- “I watched…”**

- “Master of many styles…”**

- “My brother the dr called today…”**

- “Gloze”*

- “20:02 20.02.2002″ (Not a right word…”)**

- “Lizard Song”**

- “Colleague Didactics”**

- “if you wanted to put yrself thru phd torture – mcgill or suny?”**

- “The great works…”*

- “The Kings and Queen of Qawwali chants”**

- “An Apology to François Hubert”**

- “When every hand is styled”**

- “With…”

- “‘you can pick up yr share…'”**

There are a number of these soughnoughts I’m moved to share: “Master of many styles…,” a favourite of Rui Chafes, an eminent sculptor from Portugal I met at the Villa Waldberta in Summer 1997, or “if you wanted to put yrself thru phd torture – mcgill or suny?” my friend the Munich-based novelist and publisher Georg Oswald lauded for its modernity, but one, published in Grand Gnostic Central, has proven to be “a fan favourite,” “I know the aurora borealis…,” which you can read, and hear, below:

Next month: Tanchaz!

Hell’s Printing House: For a Few Golden Ears (2004)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

I had published my first trade edition Grand Gnostic Central and other poems in 1998, and I was feeling the growing lag between that publication and what would be next, Ladonian Magnitudes (2006). At the same time, it was becoming increasingly impressed upon me not only how relatively small was the audience for poetry, but how much smaller the circle of my own readers seemed. Taking heart from Allen Ginsberg’s having composed Howl for his “own soul’s ear and a few other golden ears” (a sentiment echoed by Cseslaw Milosz, “I was convinced that we write for perhaps about twenty or thirty individuals, for our fellow poets”), I gathered fifteen poems, published and unpublished, explicitly dedicated to or otherwise written for those lovers, collaborators, friends, and acquaintances in that small circle.

The collection opens with what I have variously called ‘sonots’, ‘soughknots’,or ‘soughnoughts’ in parody of the many books of sonnets being published by anglophone Canadian poets at the time. For a Few Golden Ears gathers, as well, “condensations” (poems composed by making couplets of the first and last lines of another poem’s stanzas), collage acrostics, “quotation” poems stitching together lines overheard, “cubist” poems playing out all the definitions of the words in the poem’s title, letter poems and poems from letters, long-lined rhapsodic poems, curt images, and a manner of abuse poem. All but five of these were to be included in Ladonian Magnitudes (those orphan poems are indicated by ‘*’ below). Those golden ears were and are found on the heads of Rainer Christ, Laszlo Gefin, Ty Hochban, François Hubert, Daniel O’Leary, Georg Oswald, George Slobodzian, Zsolt Sörés, Andrea Strudensky, and my wife, Petra—and, of course, anybody else with “golden ears” to hear!

Contents

- An Apology to François Hubert*

- In the Rialto Before Prospero’s Books*

- See Garden

- Decay Pattern

- C B Hsien Hue on Woman*

- Of Poundysseus

- From a Letter

- Das München Mädchen

- Dream Notes (Bochum, 20 May 1997)

- Reasons Why

- Elenium

- A Visitor from Jerry-Land

- Poésies*

- Epistle to Zsolti: Sunday 25 January 2003

- “For years you’ve been…”*

- Pisces

Yeats observes that “We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.” “A Visitor from Jerry-Land,” however much an argument with its interlocutor, is, I argue, very much poetry:

Though I’ve shared “Reasons Why” before, I post it here again with a new recording, as it is probably the one poem of mine I wish had a wider hearing, especially in my home province of Saskatchewan. The poem is a kind of apologia. In the course of a conversation with my old teacher poet friend Laszlo Gefin, he pointed an accusative finger at me and exclaimed with a mixture of surprise and disapprobation that I was “some kinda universal welfare Tommy Douglasite!” The ensuing poem seeks—as much for myself as my accuser—to explain why.

Next month: A Crow’n’ ‘o Sough Noughts (2004).

Crosspost: Three “occult” poems

A post concerning the place of “the occult” in my poetry, with readings from three poems from Grand Gnostic Central, Ladonian Magnitudes, and March End Prill.

Read, and hear!, here.

chouette Number One, Spring 2024 is live!

chouette, a new, online literary periodical based in Montreal has published its first number. It includes, among much else, two poems of mine, “Simulacra” and “A lot of poets…” along with a poem by a student of mine, Carla Frey. You can read chouette, Number One, here.

As well, I’ve recorded “A lot of poets…” for your listening pleasure, hearable, here.

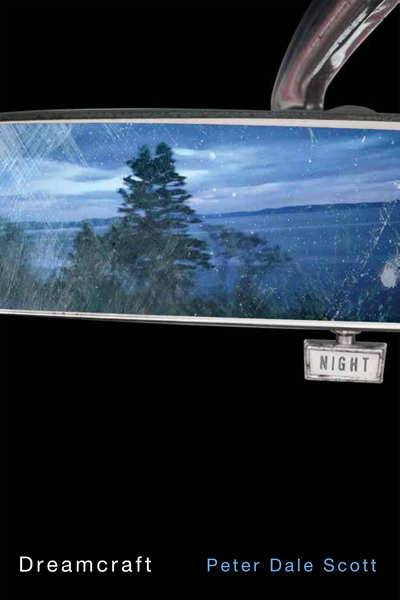

An Old Man’s Eagle Mind: on Peter Dale Scott’s Dreamcraft

The publication of Peter Dale Scott‘s latest volume of poetry is bookended by last year’s appearance of his study of Czeslaw Milosz, Ecstatic Pessimist, and this year’s release of Reading the Dream: A Post-Secular History of Enmindment, quite the trifecta for a man who turned ninety-five in January of this year (2024).

The poems collected in Dreamcraft, on might say, have vista. This latest volume’s being published in the poet’s ninety-sixth year, it comes as no surprise to find poems on old age. “Eros at Ninety” is both humbly, humorously self-deprecating and wise. “A Ninety-Year-Old Rereads the Vita Nuova” and “After Sixty-Four Years” ruminate over the changing experience of art, here, that of Dante and Grieg, within a lifetime’s perspective. The longer one lives, the more acquaintances one loses to death: elegies for lost friends—Robert Silvers and Scott’s lifelong friend Daniel Ellsberg, among them—take up nearly a third of the book. Four poems are addressed to Scott’s friend, Leonard Cohen, the book’s title track, “Dreamcraft,” the explicit elegy “For Leonard Cohen (1934-2016),” “Commissar and Yogi,” and a poetic back-and-forth the two shared just before Cohen’s death, “Leonard and Peter” (included, as well, in the last collection of Cohen’s work, The Flame). The volume’s perspective, from within “the long curve of life” (words from the book’s first poem, “Presence”) is evident in the poems that embed the poet in larger processes, whether “the bicameral brain that makes // obsfucation of mere fact / so much more beautiful” (“The Condition of Water”), our genetic character (“Dreaming My DNA”), the Earth itself (“Deep Movement”), “cosmic space / …knowable / by those specks of light // at great distance from each other,” or History’s ethogeny, which Scott glosses as “cultural evolution” (“Moreness”). Loss and the long view bring the poet’s closest relations into focus in more intimate poems, those for his daughter, Cassie (“To My Daughter in Winnipeg” and “Missing Cassie”) and wife, Ronna Kabatznick (“Enlightenment” and “Red Rose”).

Last year’s publication of Ecstatic Pessimist: Czeslaw Milosz, Poet of Catastrophe and Hope reveals Milosz as a kind of éminence grise in Dreamcraft (and, indeed, throughout Scott’s poetry). Though their friendship at the University of California, Berkely, was short-lived (roughly from 1961-1967), Milosz’s notions of the function of poetry and the poet, as one whose “poetic act both anticipates [an emancipated] future and speeds its coming,” are determinative: anyone at all familiar with Scott’s poetry and prose will hear the echo of Milsoz’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech: “In a room where people unanimously maintain a conspiracy of silence, one word of truth sounds like a pistol shot.” Scott’s lifelong relationship to Milosz’s poetry and thought, if not with the man, finds expression in the five-part sequence “To Czeslaw Milosz,” wherein Scott reflects on that relationship, one Polish word or one poem or idea at a time. This sequence is balanced, as it were, by “The Forest of Wishing,” originally published in 1965, which addresses (among other things) Milosz’s reaction to the American Counterculture of the 1960s in an earlier style of Scott’s, remarkable for a more elusive density of suggestion than is found in his poetry from Coming to Jakarta (1988) to the present volume.

Scott’s mature style might be said to take its cue from Milosz’s admonition (also from his Nobel Prize acceptance speech) that the poet need “liberate [themselves] from borrowed styles in search for reality.” The result, in Scott’s case, is sure to irritate those readers who need their poetry to “tell it slant” (whether that spring from a post-Eliotean prejudice for “metaphor” or a post-Language demand that the linguistic medium be estranged, if the aesthetic inclination is even so self-aware). A case in point might be the poem “Pig”:

Aside from the poem’s being a recognizably generic “lyric” (a first-person anecdote climaxing in an epiphany), I can well imagine readers with a taste for the mimetic virtues of, say, Seamus Heaney, Eric Ormsby, or (more recently) Kayla Czaga, or the verbal deftness of Michael Ondaatje at his best, dissatisfied with the description of the pig’s butchering (in the second, third, and fourth tercets), desiring in place of, for example, the words ‘slaughtered’, ‘cutting’, and ‘squealing’ at least a more sensuously robust diction if not a vividly inventive image to present rather than refer to the action. Such readers would be even more scandalized by the poem “Mythogenesis” with its opening “The OED defines / both mythopoeia and mythogenesis / as the same: the creation of myths,” lines which set the tone for the explicatory prosaicness of the poem that follows (a prosaicness, however, that slyly reproduces, line for line, the original email sent to the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary). I, too, have struggled for my own reasons with this tendency in Scott’s style over the years, and, were this notice a “review,” I’d be obliged to indulge in the workshop nit-pickery that would find fault with (“criticize”) a certain word choice here, a syntax that might be made more mimetic there, or even the collection’s title, but such an approach too often merely brings into view the reviewer’s prejudices or limitations (let alone the hatchet they might have to grind) than serving to illuminate the work under consideration (a problematic addressed, in fact, by the book’s penultimate poem “A Quinkling Manifesto”). Scott, himself, has responded to critics who find his poetry too prosaic, reminding them the same accusation was levelled at the prosody of Williams Carlos Williams a century ago. One could point to that other compositional sensibility (with which Williams was briefly associated) present in the “Objectivist” poets (notable for their engagement), among them, Lorine Niedecker, Carl Rakosi, or Charles Reznikoff. But more to the point, it is precisely this clinamen of Scott’s style, the way it swerves from any such obvious borrowings or influence, that is an index of that essential drive in his entire oeuvre, a “search for reality,” the telos of his work that is the principle measure of its success or failure, if a critical judgement is indeed called for.

As I’ve observed, the poems in this latest (if not last) volume take the perspective of “an old man’s eagle mind” (as Yeats called it), wherein “the long curve of life” becomes visible, the horizon for whatever else might come into view. This perspective is, perhaps, no more evident than in the book’s final, thought-provoking poem with its explicitly ethogenic theme, “Esprit de l’Escalier“:

The poem, in post-secular fashion, has as its epigraph a verse from the Book of Zechariah (4:6) (Scott the first to my knowledge to articulate a post-secular sensibility, in advance of Habermas’ developing the concept in its present form in 2008), a verse with tonal implications for what follows. We are admonished to “not just talk about politics // which let’s face it / we can do nothing about” (at least those of “us here / at this Chanukah table”) but “about culture // preparing people’s minds / for tomorrow’s revolution” (words which, again, echo Milosz’s “The poetic act both anticipates the future and speeds its coming”). Curiously, the poem speaks of a “black windshield” (likely the image that, in part, inspires the book’s cover art) “smeared… // with the grime of facts,” a brow-furrowing sentiment to flow from the pen of so assiduous a researcher, whose work, prose and poetry, has laboured to uncover that “conspiracy of silence” and scatter it with a resounding “word of truth.” (That is, perplexing as long as we remain insensitive to the potential tonal complexity of ‘facts’ and the even more important and profound distinction to be made between “facts” and truth…). This grime is to be cleaned “with hope,” a hope that waits for “the great poet // on whose shoulder / that eagle flying / above and ahead of us // in the darkness / will come down briefly to rest.” These lines are richly suggestive. On the one hand, they mark Scott, I think, as one of those increasingly rare poets who demand poetry play an orienting if not guiding role in culture and society. On the other, that “eagle flying / above and ahead of us” is at first elusive as allusive. Is it a mere—if complex—metonymy, invoking the eagle’s powers of sight? Does it allude to the eagle formed by the just souls in the heaven of Jupiter in Paradiso XIX? Is it a symbol of God, via the bird often associated with Zeus (‘Z-eus’, ‘d-eus’ (which, regrettably, only rime with ‘th-eo’…))? More tentatively, it brings to this mind, anyway, the idea of the kommende Gott, the “coming god” in Hölderlin’s “Bread and Wine” (however much that god is, in fact, Dionysius…), perhaps that god who is the only one “who can save us” in Heidegger’s late, portentous phrase. This interpretive question is resolved, however, by turning to Reading the Dream, where we discover Scott’s eagle alludes to the spirit of Rousseau in Hölderlin’s ode to the French thinker, that “flies as the eagles do / Ahead of thunder-storms, preceding / Gods, his own gods, to announce their coming” (“wie Adler den / Gewittern, weissagend seinen / Kommenden Göttern voraus“). The rich figurative resonance of these lines that demands such learned, interpretive labour marks them, too, as belonging to a past, if not passed, poetic, one rarely practiced today, if at all.

For many, I think, Scott’s vatic stance in this poem (however domesticated in its opening scene) and the faith in poetry it expresses will place him beyond a certain pale. The present, at least North American, mood is more skeptical. Those with some historical sense will too easily remember those poets who aspired to influence, cultural, social, and political, and went “wrong, / thinking of rightness.” Auden’s words, “poetry makes nothing happen,” still express a common sentiment, and, for those who do engage the question of the relation of poetry and politics seriously, it remains an open-ended, complexly recalcitrant problem. In his defense, Scott, in Ecstatic Pessimist, invokes Virgil, Dante, Blake, Shelley, and Eliot (6). More forcefully, Scott’s study of Milosz is a sustained argument for the potential social force of poetry, exemplified by his subject, notably “his contributions in the 1950s and 1960s to what became the intellectual culture of Solidarność” (5). What is striking is how this last poem in Dreamcraft departs from Scott’s characteristic poetry-of-truths that ring out like “a pistol shot.” It might be argued that its prophetic vision, of that mysterious justice-to-come and its poet, draws on poetry’s power to posit the counterfactual (how matters could or should be, to paraphrase Aristotle), to imagine a non-place (u-topos), a place that is not because it is only yet-to-be, and only potentially so. In contrast to the probing of uncomfortable truths (facts) characteristic of so much of Scott’s poetry, the fictionality of the poem’s vision (its being (only) imagined) invites, demands, a suspension of disbelief (the condition of imagining what is not as if it were), evoking our Negative Capability, that ability to live “in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” By its very unreality, then, the poem evokes that resolve that poetry—and social action—require….

That Scott’s oeuvre in this way, from his Seculum trilogy to Dreamcraft, demands the engaged reader to consider and wrestle with the art of poetry, poetry and politics, investigative fact and visionary fiction is evidence of its sophisticated achievement. Such reflection, it has long seemed to me, is the condition for any understanding of poetry, worthy of the name, an understanding that needs precede any critical appraisal. This resistance to a ready assimilation to existing literary-aesthetic canons—despite the surface, apparently-prosaic transparency of the poetry—testifies to Scott’s poetry’s being poetry, making, creating works possessed of a novel uncanniness that adds something new, not merely accomplished, to the world of letters, if not the world-at-large.

(If so moved, you can purchase a copy of Dreamcraft by clicking on the book’s cover, above.)

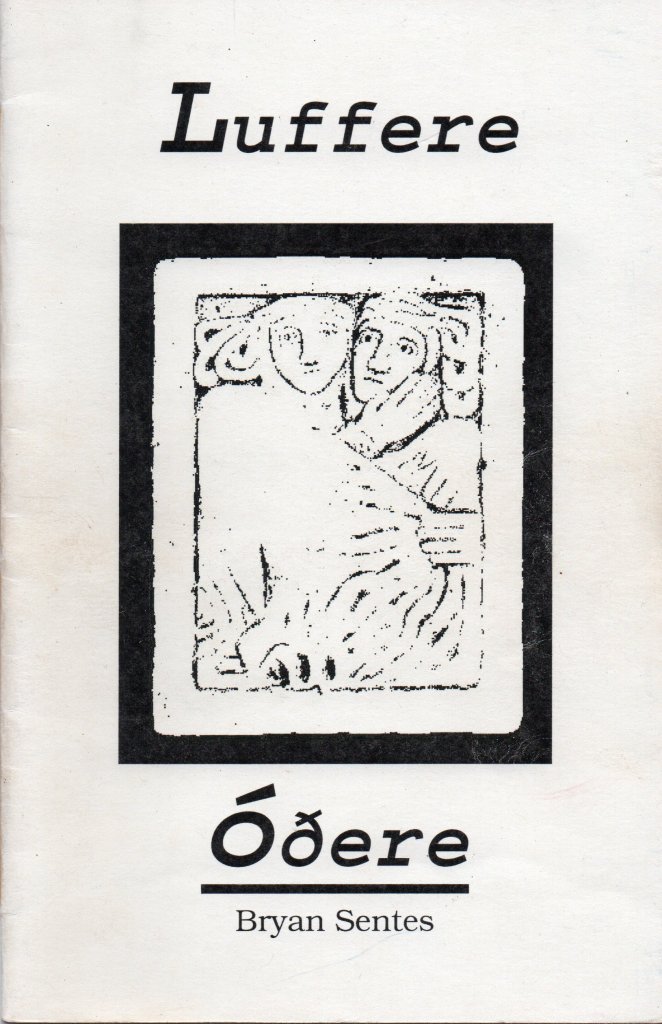

Hell’s Printing House: Luffere & Oþere: Amoretti from Marchend Prill (2003)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

The first five chapbooks I’d bound were made to collect and “publish” work otherwise unpublished in periodical or book form. Luffere & Oþere marked a departure, as it was the first chapbook that collated the poems I was to perform at a reading. At the time, Ilona Martonfi organized (among many other events) an annual Valentine’s Day reading, “Lovers and Others,” and kindly invited me to read. I don’t remember exactly what reasons I gave myself at the time, but it seemed somehow appropriate to have the poems I would read ready in print-form for interested parties, a good opportunity to issue a new chapbook, a practice I was to maintain for many years. Luffere & Oþere are the oldest forms of the words ‘lovers’ and ‘others’ in English.

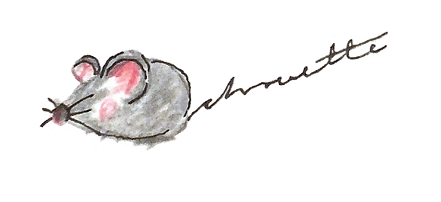

Not only was this chapbook the first made for a reading, but it is also the first with original artwork (in this case, two collages) for the flyleaf, outer and inner:

However much amor is one of the great poetic themes, it’s not one I have often dared (except for one poem, known only to my closest friends). However, at the time, I had written a poetic sequence, an extension of the concerns motivating X Ore Assays and Seventh Column, that was to be published years later in 2011 by Book*hug, March End Prill. This sequence, compositionally, adhered to a resolutely Surrealist poetic (“the dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason and outside all moral or aesthetic concerns”), informed as much by Breton as by ethnopoetics:

Songs are thoughts, sung out with the breath when people are moved by great forces & ordinary speech no longer suffices. Man is moved just like the ice floe sailing here and there in the current. His thoughts are driven by a flowing force when he feels joy, when he feels fear, when he feels sorry. Thoughts can wash over him like a flood, making his breath come gasps & his heart throb. Something like an abatement in the weather will keep him thawed up. And then it will happen that we, who always think we are small, will feel smaller still. And we will fear to use words. But it will happen that the words we need will come of themselves. When the words we want to use shoot up of themselves—we get a new song.—Orpingalik

At any rate, I combed through March End Prill and abstracted a sample of, if not all, the poems defensibly “erotic.” The titles are their first lines or the first words thereof:

Contents

- falling asleep

- she was coming for supper

- durée

- dear Wife

- we must really be out of touch

- Can’t wait for you

- mornings spooned

- When I get the chance

- my old friend dumped his

- Godammit! Love’s

- Bedrock

Here’s a new recording of these poems, for those who missed the reading!

Next month: For a Few Golden Ears (2004).

One for chouette

chouette, a new, online literary periodical based in Montreal, has kindly accepted two poems of mine for its inaugural issue.

One of the these poems, “A lot of poets…,” I record, here. It’s a versification of a colleague’s Facebook status from the opening days of the Pandemic. Thanks, again, to her, for allowing me to set her words to “the music we sing what we have to say to.”

On George Slobodzian’s Apokryfa

Culture must be—as the word itself might suggest—cultured, seeded and carefully tended. Such care takes many forms in Canada, from ever-diminishing (if however appreciated) government funding, to the selfless, meagrely-rewarded efforts of those who—in the case of our literary culture—publish small magazines and books of poetry, to more grassroots efforts.

In recent years, in Montreal, Devon Gallant and collaborators have cultured an urban poetic garden, organizing the Accent Reading Series, which combines an open-mic (as polylingual as the city) and a spotlight on one or two featured readers, and which has, accordingly, gathered a small, poetic community. One of the fruits of this endeavour is Cactus Press, which, to date, has issued over thirty chapbooks and the first trade edition of the unnervingly-talented Willow Loveday Little, (Vice) Viscera (2022).

One of the newest of these chapbooks is George Slobodzian’s Apokryfa, his second with Cactus Press. Apokryfa gathers eighteen poems, old and new, organizing them in three sections, “In the Garden,” “Et Homo Factum Est,” and “Tale.” The first reflects on childhood and youth, the second works up and on, more-or-less, Catholic mythology, while the last reworks fairy tales. However much at first glance these sections might suggest a progression from autobiographical truth to overt fiction, a more canny, poetic sensibility is at play that subverts such too-easy, hard-and-fast distinctions.

But this sophisticated sensibility is only one aspect of these eighteen poems, which, perhaps more importantly, reveal a poet at the top of his game. While, from the “Tale” section, “Other Dwarves” and “Deliverance” (a riff on “Rapunzel”), might seem relatively light, they are not without their wit (in the case of the former) or rich suggestiveness (in the case of the latter). Most of the poems are, however, so to say, more thematically substantive. “Radisson Slough,” recounting how the boy speaker “Out hunting with [his] father / and brothers, …was the dog,” concerns as much a moment in one’s lifelong loss-of-innocence as much as, perhaps, weightier epistemological matters when “in search of the warm reward / of a grain plump duck,” the boy finds “instead the corpse // of an abandoned crane / half-submerged and corrupt, / its great wings still engaged / in a sort of flight until” he touches it, and it sinks. “The Annunciation” in the chapbook’s second section, “Et Homo Factum Est” grimly recasts the Archangel Gabriel as the agent of some unnamed totalitarian regime with an uncannily ironic gift of prophecy who foretells the life of the expected son, a malcontent (and who wouldn’t be under such a system?) who leads “an entirely unremarkable childhood,” in the end only to “be taken / into the appropriate custody” to finally succumb “to his diseases.” And, in the book’s final section, that persistent question if not problem of “the Subject” (however much presently eclipsed by that of Identity) is taken up in a sly play on Delmore Schwartz’s “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me” in “4th Bear” and the provocatively reflexive “Tale” (which begins: “in a dark forest I found you / not knowing you were / the dark forest and the trail / I was following was the trail / I was making those were / my own breadcrumbs…”).

Those with poetic ears attuned to melopoeia will already have remarked the deft, phonemic harmonies of “the warm reward / of a grain plump duck.” Slobodzian’s undeniable prosodic gift (which I have previously remarked), though present, is at once more under- and overplayed, as it were. Though passages of the quality of that from “Radisson Slough” are not infrequent, the language tends to be plainer, shaped more by rhythm than harmony; at the same time, there is, at times, a marked deployment of rhyme (especially in “Rapunzel”). But Slobodzian’s talent and artistry all come together perhaps nowhere most markedly as in “Pysanka (The Written Egg),” from the book’s first section. Here, a boy, barely out of infancy, sits with his grandmother as she draws a stylus “across the surface / of an Easter egg,” while the boy watches. The poem is a small tour de force in the ease with which it delineates a primal moment of culture (the grandmother’s “fingers [know] these things” and take the boy’s hand) and, reflexively, poiesis itself in the image of “the risen sun / a flaming rose / above an endless line.” These three lines should suggest just how extended an exegesis and appreciation the poem calls for.

Gallant and Cactus Press have surely done us a service in collating and sharing this handful of poems. One can only hope there is some acquisitions editor at a trade press with the savvy to offer to gather them into that full-length volume we’ve been waiting for for too long.

“Hell’s Printing House”: Seventh Column (2001)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

Saturday 22 September 2001 The Globe and Mail published an essay article by John Barber “Wounded and left on Afghanistan’s plains” (F4). Despite its critical stance toward the then-impending invasion of Afghanistan by coalition forces, the terms of its discourse were so pedestrian my frustrated and bored eye wandered across its six columns. The article read thus, against the grain, appeared oracularly clear, and the experience of that reading what I wanted to communicate in the resulting poem. The sense this reading made to me leaves its trace in minor editorialisations (where the text has been stepped on). This vision into the essence of our imagination of Afghanistan is as forbidding as the country itself: a land of glacierous and desert mountains and sandstorms and tire-melting heat that swallows whole armies. “Cut the word lines and the future leaks through.” Here, English speaks this vision: in dead or obscure words, new compounds and coinages. Syntactically, at root (or so Norman O. Brown told John Cage) the arrangement of Alexander’s soldiers in a phalanx (the Great, too, stopped in Afghanistan), the language has been demilitarized.

Soon after I had composed the poem and printed and bound it in chapbook form, The Capilano Review called for submissions for a special issue “grief / war / poetics” that responded to the then-recent 9/11 attacks. It kindly accepted “Seventh Column,” just not the whole thing, so I had to decide how to excerpt a poem that, despite its disruptive, disrupted syntax, was still, arguably, a “whole.” I opted to have TCR print the first eight and last six stanzas to create a manner of sonnet. That excerpt can be read here, a reading of which I share, below.

“Seventh Column” is, to my mind, a high water mark of my poetic practice, the most carefully, rigorously composed of any of my poems. The lineation and punctuation intentionally follow no consistent rule (some lines are end-stopped, others enjambed, some sentences begin with capitals and end with periods, others not…); words are sometimes broken into their syllables, resulting in new coinages or echoes of an older English (whose meanings are footnoted). The language is thus “made new” and impossible to dominate or domesticate by a hermeneutic will-to-meaning lacking sufficient Negative Capability. Indeed, the poem eluded even my own compositional rigor, somehow making itself circular, ending with the suffix ne- and beginning with the root -glected…

Next month: Luffere & Oþere

New Poem up at Montreal’s own Columba

As my friend Erin Mouré writes, “Aye Columba!” Montreal’s own online poetry periodical has been kind enough to publish a poem of mine along with those of four others, one of whom, Domenica Martinello, was once a student of mine—nice to be in such fine, poetic company!

What’s especially gratifying is the poem selected by Columba‘s editor, Emily Tristan Jones, “Poetry, here, meaning: whatever language helps you sleep at night,” a kind of breathless, dithyrambic work, long a favourite compositional mode of mine, but one ever less frequently indulged.

You can read that poem, and all the others in this Fall edition, here.

Shelf Portrait

The good folks at The Richler Library Project at Concordia University have shared my “Shelf Portrait,” a brief piece on my home library. The essay ranges over the contents, organization, and use of my books and includes a few, choice pictures.

One addendum, mind you: the photo of a sample of my ufological library, is hardly of “Works on cosmicism, astrology[?!], and space exploration, among other celestial subjects“!—It’s all about UFOs and related matters from a wide variety of angles!

You can read my Shelf Portrait, here. Why not browse all the others, here?

Much gratitude to Jason Camlot, scholar, poet, and musician, for soliciting the piece.

“Hell’s Printing House”: X Ore Assays (2001)

Aside from the pages of little magazines and those of certain, indulgent anthologies, by poems really first made their way in the world in the form of chapbooks. I hadn’t yet published a full-length trade edition, when I went on a “European tour” in 1996, reading in Munich (twice), Heidelberg, and Amsterdam, two self-published chapbooks, Gloze (1995) and On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), my calling cards.

Joachim Utz, the sponsor of my reading at Heidelberg University’s Anglistiches Seminar, observed that my chapbooks reminded him of William Blake’s. This new category of post takes its inspiration from his remark. “Hell’s Printing House” will showcase my chapbooks, describing them, detailing their contents, linking poems that have already been published at Poeta Doctus, and presenting a new recording of one of their poems.

It is hoped these posts fill the lacunae between full-length collections, assuring those (apparently) few (and valued) readers who follow my production with interest that I am hard at work, going my own direction, at my own pace, trusting those intrigued might be charmed enough to tarry along….

In 1998, I published my first trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems, which collected most of the poems in my previous chapbooks, other than those in On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (which can be accessed here under the ‘Orthoteny‘ tag). I continued to mine and open new compositional veins in line with what I had written, but embarked in a totally different direction in late 2001 with X Ore Assays, which takes inspiration from a number of sources. The most immediate is FEHHLEHHE (Magyar Műhely, 2001) by the Hungarian musician, archivist, editor, writer, and cultural worker Zsolt Sőrés. FEHHLEHHE deploys a wide, wild range of linguistic disruption: disjunctive syntax, polyglottism, collage, sampling, homophony, and portmanteau words, among other means. X Ore Assays is in part an attempt to engage Sőrés’ text in kind, wrighting an English that would imaginably answer his Hungarian. A more remote but profounder influence is the homophonic style that myself and the late Dan Philip Brack (DPB) corresponded in, portions of which were intergrated into his series of short prose works, Letters from Jenny. In our correspondence, very few words were spelled in anything other than a pun, a delirious, funny, private literature, a practice whose linguistic energy I desired to tap in composing the project whose working title came to be X Ore Assays. An even deeper inspiration was the surreal practice of William Burroughs in writing “the word hoard” that was reworked and worked up into his breakthrough novels Naked Lunch, Interzone, The Soft Machine, The Ticket that Exploded, and Nova Express. I aimed to cleave close as I could to that first definition of Surrealism: “Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation,” a much more fraught practice today than over two decades ago. The working title was motivated by this experiment: the texts, composed daily, would comprise a score (x-ore) of raw material (ore) to be assayed, measured, graded, and perhaps refined. However, a kind of ironic, poetic justice intervened. One of the days in this open-ended practice fell on September 11, inserting these texts radically and irretrievably in time’s flow. Curiously, that day was not immediately remarked; rather, hearing of, I think, Billy Collins’ refusal to write of the event almost a week later spurred, ultimately, fourteen more days of response, a supplemental sequence provisionally titled “Sewn Knot.”

That initial twenty, as a gesture of homage, I sent to Sőrés, who arranged to have them published in the Hungarian-language avant garde journal Magyar Műhely. “Sewn Knot” appeared, thanks to efforts of the editor-publisher of Broke magazine Andrea Strudensky, in the Canadian periodical dANDelion. “X Ore Assays” and “Sewn Knot” have presently been combined and are being revised and refined under the working title “after FEHHLEHHE,” which makes up the opening section of a manuscript-in-progress tentatively titled Fugue State.

The sections responding in real time to 9/11 were not among those included in the chapbook; they can, however, be read, here. I reproduce, below, a page from the middle of the book, and read the day’s work beginning “Wit noose Airecebo..”

Next month: Seventh Column (2001).

Crosspost: from Orthoteny: a work in progress: Magonian Latitudes

Here, I share a sequence of poems from my second trade edition Ladonian Magnitudes, “Magonian Latitudes,” which, among other things, relates tales from the Middle Ages of Sky Ships and their crews and their interactions with mortals. You can read—and hear!—the poetic sequence, here.

Crosspost: from Orthoteny, a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: closing cantos

Here I link to the closing cantos of a long section On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery from a long work on “the myth of things seen in the skies,” Orthoteny.

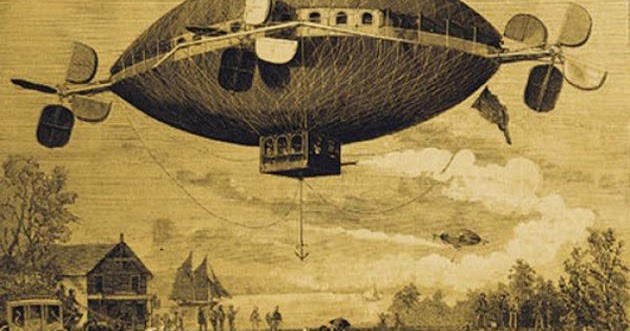

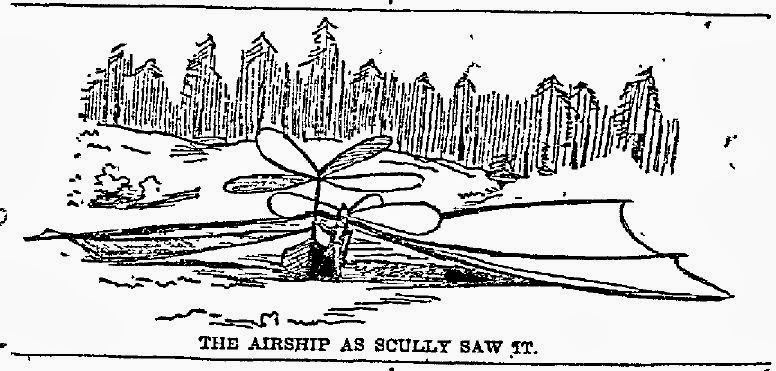

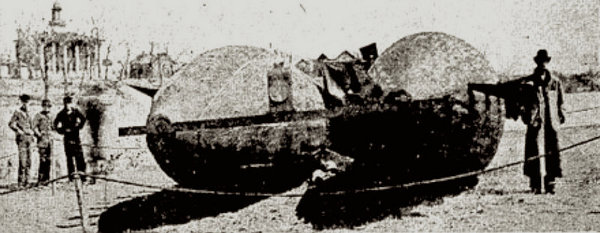

Following the Mystery Airship flap of 1896/7, as real airship technology slowly took off, sightings of what seemed airships continued globally. These airships, however, were observed to outperform their real counterparts in inexplicable ways.

In the days leading up to the Great War, sightings of airships, understandably, increased. They later appeared, this time all-too-much for real, over London, in the world’s first aerial bombardment. And, just as as forerunners of UFOs were to appear in the skies over Europe and the Pacific as “Foo Fighters” in the Second War, the horrors of the Gallipoli campaign in 1915 were to inspire a myth of a mass abduction…

You can read, and hear, these three poems, here.

Crosspost: Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April 18, 19, 21, 24, and 26

Here, the penultimate cantos from a section of a long work concerned with “the myth of things seen in the skies,” Orthoteny. These cantos relate phantom airship sightings, landings, meetings with their pilots, and debunkings from a prototypical UFO “wave” that occurred in April, 1897. These tales are of interest for including (among other things) the first report of a cattle mutilation and the story of an airship dragging an anchor, which echoes a tale from the Middle Ages!

You can read these poems, and hear them, too, here.

“statements, terms, and jargon”: Tuesday 17 October 2023

Time constraints and temperament restrict many of my thoughts to remarks. Thus, what follows are emphatically fragments, metonymies (parts) of potentially more-extended discourses and drafts (essays) holding the promise of future elaboration….

The debate over the origins of the coronovirus continues four years after the pathogen’s emergence. Whether the virus “leaked” from a lab or originated in a wet market is false dilemma, however. Gain-of-function research is carried out to help predict how virusses that originate “in the wild” might mutate and effect human beings; wet markets are precisely a vector for such virusses. At base, both sites are situated in a dysfunctional food production system “linked [as Hadas Thier puts it] to the rise of factory farming, city encroachment on wildlife, and an industrial model of livestock production.” Thus “the debate” is a distraction from the real, material conditions that gave rise to Covid-19 and that culture future pandemics…

Presently, Quebec’s civil service unions are negotiating a new contract with their “employer.” What is as remarkable as it is unremarked (such silence an index of ideology) is the adversarial stance adopted by the provincial government. It seems not to understand that a robust and efficient civil service is not an “expense” or “cost” to the province. An effective civil service would, first, deliver needed services to the population, which would culture a happier population, one would think, rather than one for whom life is made increasingly difficult if not downright precarious. And wouldn’t a governing party want a happier populace? But, moreso, an investment in the civil service is a cash-injection in the province’s economy, not a drain on the government’s monetary resources. In the first place, a non-trivial portion of wages and salaries are immediately recouped as income tax. What remains of the wages and salaries is, for the most part, spent on local goods and services (and the resulting profits are themselves subject to taxation). If the civil servants are fortunate enough to have any surplus monies (a majority of Canadian households run a debt), those funds are deposited in local financial institutions, banks or, ideally, credit unions, which, then, in turn, are leant out as a further cash injection into the province’s economy. And what is most egregiously overlooked is that the province’s civil servants are themselves tax payers—that group always appealed to to keep governments’ “operating costs” low—and most importantly citizens.

“Populism is always ultimately sustained by the frustrated exasperation of ordinary people, by the cry, ‘I don’t know what’s going on, but I’ve just had enough of it! It cannot go on! It must stop!’ Such impatient outbursts betray a refusal to understand or engage with the complexity of the situation, and give rise to the conviction that there must be somebody responsible for the mess—which is why some agent lurking behind the scenes is invariably required.”—Slavoj Žižek, First as Tragedy, Then as Farce (New York: Verso, 2009), 61.